Avocado

Homes and the land they sat on were more self-sufficient at the middle of the last century than the are today, and my grandparents bought the one bath, two bedroom frame and stucco house for less than $5000 in 1950, partly because of the existing fruit and nut trees on the quarter acre lot, and the two rows of table grapes, one honey gold Concord, one deep ruby blue Ribera, both delicious. These grew along the south property line where old Mr. and Mrs. Powers lived.

On the north side, next to the Scrugg’s, were two rows of citrus trees: oranges, and a grapefruit tree, maybe two. Two English walnuts and an almond tree shaded the front yard, a Meyer lemon, another couple almond trees grew in back with some lawn to mow and a kitchen garden strewn in the spring with packets of poppy and wildflower seeds.

A vacant lot faced across the street, used by my granddad for growing corn and melons, drying and shelling the nuts, and then later, for drying the redwood cones that provided the seed that he sold to the world and added a little income to his modest US Forest Service retirement.

It was a quiet and homey neighborhood on the whole. I remember the roar of a huge nightmarish Air Force B29 flying low over town into the bright light of a full moon rising above the ridge of the Sierra to the east one evening at the end of a war, most likely the Korean, though the end of that war came as I recall while grandma and grandpa and I were in the house trailer on Lake Havasu with The Stevensons and Aunt Alice, the night I caught the flying dollar bill the wind storm blew through the banging door, the subject of another post.

And of course, in the summer, the sound of the house and yard was colored by the sound of water running. Always the sound of water running. Water splashing out on the ground from a 4 foot high, 3 inch diameter aluminum pipe stand. Water running through the cooler. Water through a hose, water splashed through a thumb to make just the right spray required for zinnias or the chrysanthemums under the carport, water rhythmically chucking through a lawn sprinkler, or just the humming sound of water through a soaker hose, lazing out the nozzle into the small irrigation ditches opened and closed with a hoe or the point of a shovel, the dirt blanched gray by the sun, then turned dark and gooey and cool by the water.

These yard ditches were Mississippi Rivers to me. They were the Nile and the Congo, they contained hours of Amazonian mud play, they were my dream world: I was a god creating London and New York and Los Angeles, cities and civilizations in the dirt, which, as if by the very rules of our strange but shared human nature, I could then destroy by flood, or, when my towers and bridges were allowed to dry to adobe hardness, blow away with the pellets of a Beebe gun. My own Fort Apache, my Saracen fortress, my little Coliseum. There were no PlayStation platforms back then; no Nintendo, no Atari, and the few pinball games around were of no interest to me. I had the universe in the mud of my grandparent’s back yard.

At the very back of the yard, back behind the garage next to where my granddad built another bed-sitting room and bath, and behind the storage room he built to rest his saddle and tack and his tools, back behind where he kept all his nails sorted by penny size in Prince Albert tobacco cans, back behind the water cooler on the back wall of the extra room grew a single and beautiful and entirely wonderful Hass avocado tree which was always worthy, almost sacredly worthy, to receive the continual and extreme high maintenance it required.

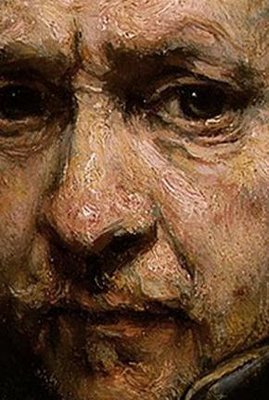

It is hot to hellish in the San Joaquin in the summer; in winter the weather will freeze, it will ruin the oranges, which meant back then the near total destruction of the local economy. It is not the best country for avocados. My granddad was knowledgeable of plant and animal life, indeed his knowledge was learned as a requirement for his survival as a both a boy and an adult. He was an expert on the trees and the land he knew, and he held his avocado tree in reverence. That he had one to cultivate was a measure to him of his worth as a man.

He knew how to count a season’s crop by the number of small yellow-green flowers that bloomed in the late winter and he knew that two, three hundred flowers meant a third as many avocado pears.

He knew when to water; he would not over water. He knew which limbs to prop with two-by-fours: the trees are tender, the flesh of the branches as easily torn as their lizard like skins, and he knew how to support the limbs with baling wire cushioned with scraps of tire and gunny sack. He bermed the trunk of the tree with a mound of dirt and a mulched topping of fallen leafs, all in a ring the diameter of the tree and the depth of half a leg.

Avocado foliage is dense and the leaves are shiny deep green on top with rusty brown undersides. The fallen leaves crackle when trod, and a heavy dust rises. They give great shade. The give off the smell of anise, of licorice. My mud world was not allowed under the avocado tree.

Grampa loved the fruit; he would pull one he’d left to ripen on the branch, or find a pear fallen to the ground. He’d smell it, and slice it in half with his pocketknife, straight and clean across the length of the hemisphere, not touching, not scoring the hard inner seed with the blade and he'd gently and quickly twist it in two to look at the meat. I don't remember him cutting an unripe avocado. He would smell it again, then cut a slice and taste it, hand over another slice to me or whoever might be with him. If there were more pears he thought ready he would bag them, store them in crates in the garage with the nuts and fruit he dried, and the olives he cured, or put them in bags to give away, or take a couple into the kitchen to my grandma.

He liked them best with lemon and a shake of salt. We mostly ate them as they were or tossed in a salad with tomatoes and crumbled taco chips. We had no idea of guacamole back then.